When I went to the Philippines 9 years ago, dengue fever was a big concern for my mom. She constantly had my sister and I cover ourselves in mosquito repellent in order to minimize our chances of getting the virus. That memory stuck with me and has now lead me to investigate the dengue virus and its proteins for my research project.

I looked to Wikipedia to give me basic information about dengue virus, (DENV) and discovered that the genus this virus in apart of (Flavivirus) contains other well-known viruses such as the West Nile virus (WNV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and Zika virus (ZIKV) [1].

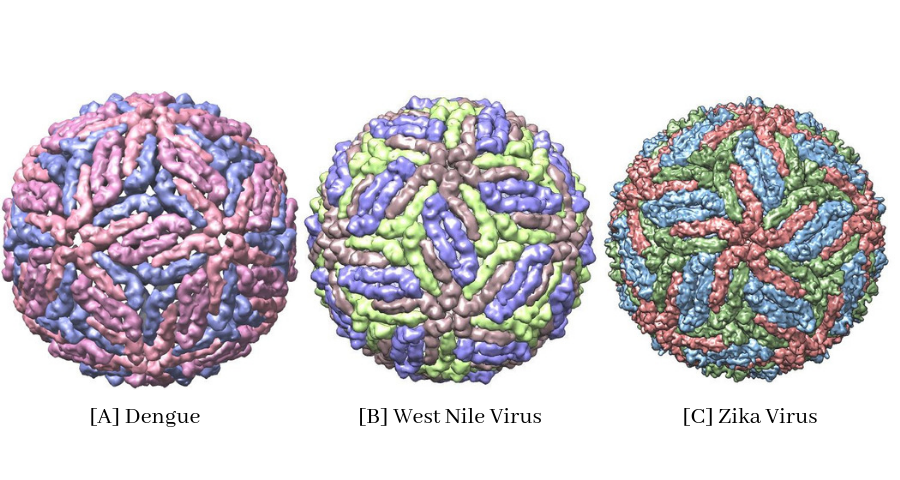

The Flavivirus genus (family: Flaviviridae) comprises over 70 small enveloped viruses, more than 50% of which are human pathogens transmitted by mosquitoes or ticks [2, 3]. They have a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome that is approximately 11,000 bases long [2,3]. Flaviviruses, in general, are small, icosaherdral, enveloped viruses, that have a highly symmetric viral membrane that contains viral envelope and membrane proteins (examples in Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1: The different structures of the viruses. [A] PDB: 1K4R [B] PDB: 5IRE [C] PDB: 3J0B

Here’s a really quick overview on how these viruses work: For these viruses to enter host cells, they must first recognize a ubiquitous cell surface molecule or receptors on the host cells and then enter through receptor-mediated endocytosis [2]. Once the pH inside the lumen of the endosome is mildly acidic, the fusion of the viral membrane and the endosomal membrane takes place [2]. This also leads to the release of the nucleocapsid into the cytosol of the cell [2]. From there, seven nonstructural proteins establish sites on the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum – allowing the viruses genome to replicate [5].

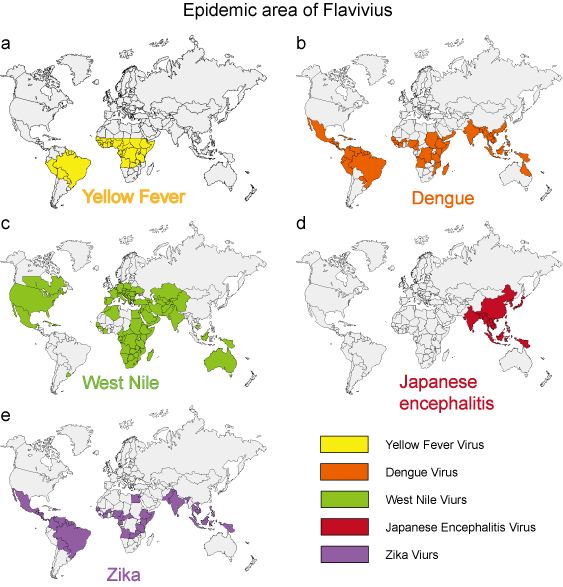

Due to the viruses main vector being mosquitoes and ticks, these viruses have spread and caused major threats to human health [4]. The most prevalent flaviviruses DENV, YFV, and more recently ZIKV use Aedes aegypti (a mosquito) as their vector [5]. This is significant as these mosquitoes have adapted so well to human activities, almost exclusively feeds on humans, and are able to to fully develop in very small bodies of water [5]. Factors such as climate change, urbanization, and human behaviours have also appeared to influence the prevalence of these viruses [4].

Figure 2: Global distribution of five of the prevalent viruses

So that’s a small look into Flaviviruses. There’s obviously a lot more information that you can find about these little devils. For more information I would recommend the fifth reference I listed below (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.029 ) as it covers more bases and has a reference list of their own.

References:

[1] Wikipedia

[2] Smit J. M., Moesker B., Rodenhuis-Zybert I., & Wilschut J. (2011). Flavivirus Cell Entry and Membrane Fusion. Viruses, 3:160-171 doi: 10.3390/v3020160

[3] Rey F. A., Stiasny K., & Heinz F. X. (2017). Flavivirus structural heterogeneity: implications for cell entry. Current Opinion in Virology. 24:132-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2017.06.009

[4] Paixão E. S., Teixeira M. G., & Rodrigues L. C. (2017). Zika, chikungunya and dengue: the causes and threats of new and re-emerging arboviral disease. BMJ Global Health. 3:e000530. doi:10.1136/ bmjgh-2017-000530

[5] Best S. M. (2016). Flaviviruses. Current Biology 26(24): PR1258-R1260. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.029

Images from:

Figure 2:

https://www.creative-diagnostics.com/Flavivirus.htm